This originally appeared on The Huffington Post.

Nineteen years ago, my wife Heather Whinna stopped by the post office on the way home. She found bins there full of letters addressed to Santa Claus, left out by the post office for people to read and answer. Curious, she read a few of the letters and couldn't believe what she saw.

These weren't impish requests for toys or a new bike; mostly, they were desperate pleas from heads of households asking for help. It was staggering. People let down by the remnants of a social safety net, without families or abandoned by their families, people suffering sickness, poverty and abuse. People so far out on a limb that they swallowed what pride they had left, took pen in hand and wrote down everything that had failed them, everything that had broken or been stolen, everything that had hurt them and made them feel fear and shame and worry.

They described anguish over their children's needs, their hunger, their lack of appropriate clothing, school supplies and other basic needs.They described homes they could barely afford to stay in, wretched though they were. They described relationships wracked by abuse, the legal system, disease and addiction. They addressed their problems to Santa Claus at the North Pole and sent them by mail into the vacuum of humanity that had left them so desperate.

It seemed impossible, yet there it was. She took one of the letters home and showed it to me. I couldn't help but be moved when I read it, and the realization that there were hundreds -- no, thousands -- of these letters changed something in me.

Between us, we put together a parcel: some clothes, some needed items mentioned in the letter, some money. On Christmas morning, we drove to an address unannounced, found the letter writer and gave her the package. We did the same the next few years for a couple of families, whatever we could manage. Heather works at the Second City theater in Chicago, and concurrent with her letter-reading, Andy Cobb, her colleague at the Second City, produced a marathon 24-hour improv show to raise money for a homeless shelter. Andy and Heather decided to combine their efforts and arranged a 24-hour show at the Second City in December, 2002 to raise money for the letters. That first year, the show allowed us to help even more families, turning Christmas morning into an all-day affair.

Meeting these people where they lived, seeing how they held their families together with nothing more than the frayed fibers of their willpower, made me want to do it again, do it more, find more of them. The places they had to live barely qualified as enclosed spaces, much less domiciles. Broken or missing windows were patched with tape and newspaper or left un-mended. Wind and snow blew in through gaps in walls and doors. A house suitable for a couple of people could be divided into as many as eight tiny spaces, each holding a family.

These people were exploited on all fronts. Recent immigrants had to suffer unimaginable indignities just to arrive, and once here be exploited by employers and slum landlords. Too afraid and vulnerable to complain or look elsewhere, they hid in death trap squalor, bound by fear. They knew to be afraid of authorities, afraid of local criminal gangs, afraid of what might happen to children they had to leave alone when they went to work, afraid for their families back home, afraid they might lose touch with children they had to leave behind, afraid that, for the most capricious of reasons, they might lose the tenuous hold they had on a potential life here.

The places the poor and afraid are forced to live--single rooms, dirt-floored basements, empty garages and storage cubicles--makes me simultaneously shudder with both the indignity of their plight and rage that there is a class of man who could extort rent for such an existence. Who is that motherfucker, that piece of shit that chases people into a basement using fear as a torch? Bring me to him so I can spit in his eye.

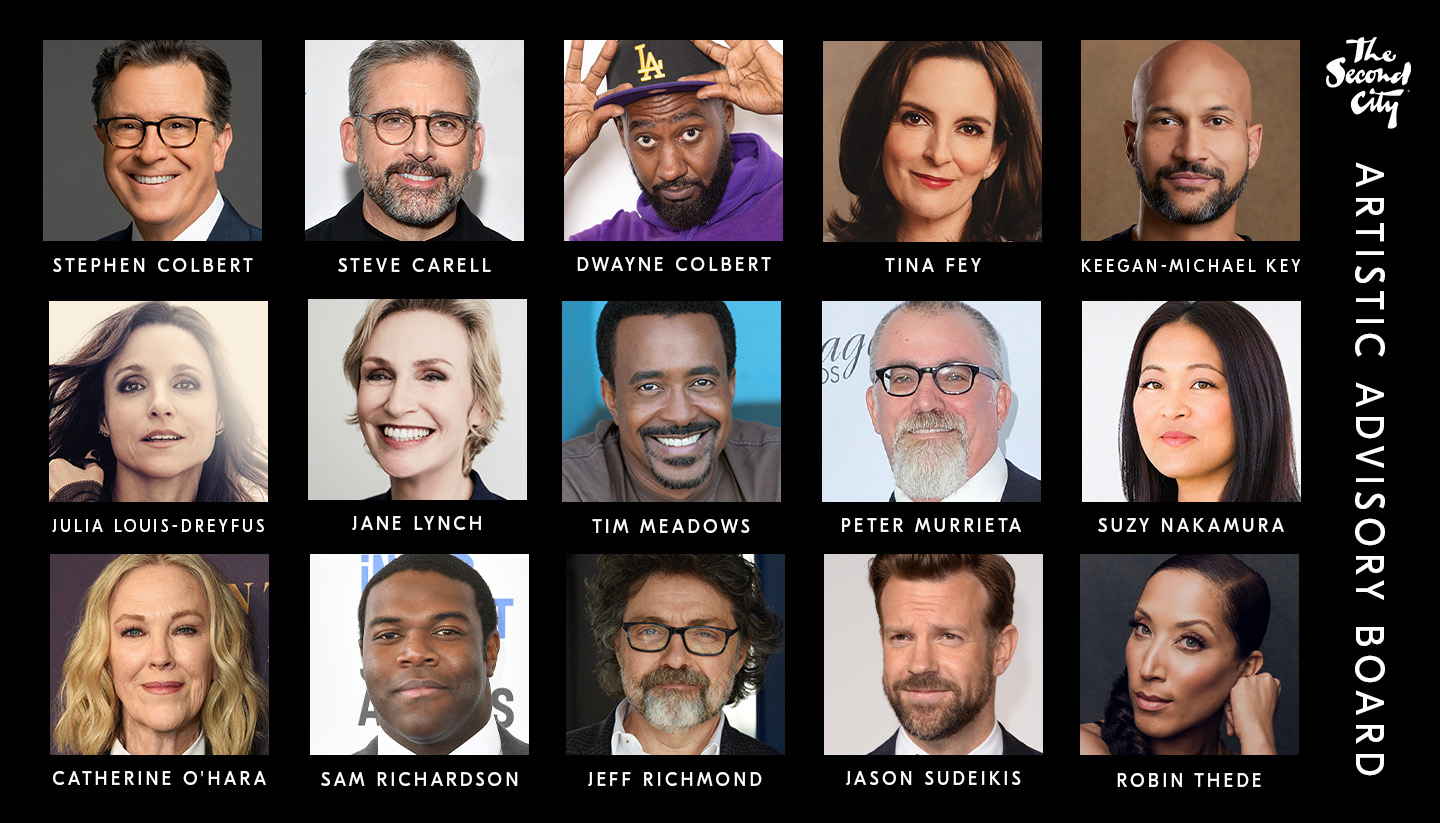

Over time, the 24 Hour show has become an annual tradition and an essential element of the culture of Second City. As it grew, it developed its own traditions. The show has musical and variety interludes, but the core improvising actors remain onstage and on their feet for the entire 24 hours. All the performers perform for no fee. Some buy themselves a ticket to the event and donate additionally through auctions and propositions. Shortly after the show was established, Jeff Tweedy joined the effort, performing and selling private concerts by auction, sometimes as many as three a year. The Second City solicits donations from its nightly audiences and matches the donated amount.

In its best years, Letters to Santa raised enough to change the trajectory of more than a dozen of Chicago's poorest families. It's an inviolable principle of the effort that every cent of the money raised goes directly to people in need, either as gifts or direct assistance. There is literally no overhead, and over the years, we have distributed over a million dollars directly into their hands. Families have been able to move into better housing and safer living conditions, solve health crises, relocate and reunite family members, and otherwise stabilize precarious lives in a way that enabled them to flourish.

The post office no longer allows full access to letters addressed to Santa, though they still collect them. There's now a preposterous official system, whereby they give you a letter with a code number and you give them a parcel and they try to mail it to the recipient for you. Most of the places we go to on Christmas don't have secure mail delivery and certainly don't have anybody free or willing to come to the door to receive a parcel. Some don't even have what you could identify as a front door.

Since this policy change, we've had to use non-governmental aid agencies to help us find families in need. We found families through the Jane Addams Hull House until it closed in 2012, and since then we've worked with Onward Neighborhood House. The extent of poverty in the city makes it inevitable that we are missing some families, families who are outside the reach of an aid organization, doubtless still addressing their need and fear to Santa Claus at the North Pole, but if the nature of need is that it is all around us, then reaching in any direction allows us to make a dent in it.

We go on Christmas because people will be home. If employed, they will have that day off. If a family is scattered, Christmas brings people home. This one day like no other brings families together, so we can be pretty sure to find everyone mentioned in the letters in one place. We go with a small group of friends, sometimes Jeff Tweedy, his wife Sue Miller and their boys Spencer and Sam, sometimes actors from the show, but always including Tim Midyett, Vickie Hunter and their daughter Lila. Lila is 11 now and has spent every Christmas of her life in a van with us delivering gifts to people she's never met before. It's literally all she's ever known as Christmas. We make a point of having someone who can speak Spanish conversationally to help convince people used to being afraid that we mean no harm when we ask them to open their doors. The last few years Fred Armisen, born in Venezuela, has come along in that role.

I haven't had a conventional Christmas morning in almost 20 years. I haven't missed it.

Steve Albini is a recording engineer, studio owner and musician.

2018's 24 Hour: To the Moon and Back, Buddies runs nonstop Monday, November 19-Tuesday, November 20 from 5pm-5pm at The Second City e.t.c. Theater in Chicago. Click here for information on how to attend, stream it live or to make a donation online.

Shows & Tickets

Shows & Tickets  Chicago Venue Info

Chicago Venue Info  Classes & Education

Classes & Education  Second City Works

Second City Works  Second City Network

Second City Network  Our Legacy

Our Legacy